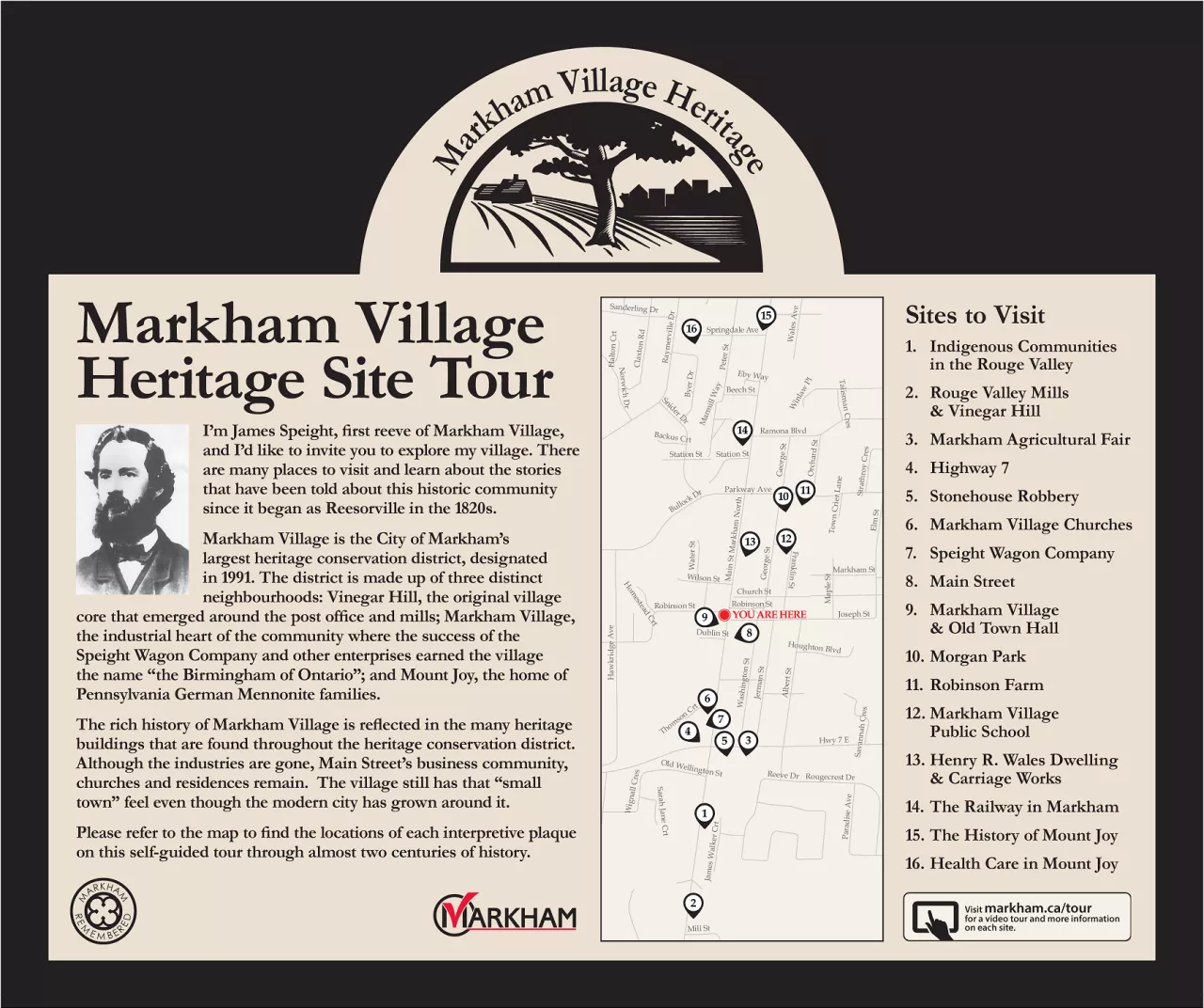

Markham Village Heritage Tour

- Vinegar Hill Subdistrict

- Markham Village Subdistrict

- Mount Joy Subdistrict

- 1. Indigenous Communities in the Rouge Valley (Vinegar Hill Subdistrict)

The Late Woodland period of 800 A.D. to 1650 A.D. spans the origins of various Iroquoian speaking tribal confederacies in southern Ontario, including the Huron, Petun, and Neutral.

Stone projectile points and tools, pottery fragments, and other artifacts have been found scattered across farmlands in the Rouge River floodplain over the past several decades. These artifacts date back to the Late Woodland Period. Concentrations of these artifacts and the discovery of ossuaries, or burial pits, point to the existence of semi-permanent aboriginal villages throughout what is now the City of Markham.

Aboriginal village reconstruction

One of the more significant discoveries was made in the 1870s by Thomas A. Milne, a local mill owner, who collected artifacts found on his farm. The mainly “flint arrowheads, tomahawks, pipes, etc.” were put on display in the office of the Markham Economist newspaper. The Milne family were still collecting artifacts from their property as late as 1921. Archaeologists believe they were from a village that once stood within what is today the Milne Conservation Area.

Another of the early archaeological discoveries was a large ossuary that was found in the 1950s on the west bank of the Rouge River, south of Highway 7. The many artifacts found prove that there was a year-round Aboriginal community in Markham long before the arrival of European settlers in the 1700s.

- 2. Rough Valley Mills and Vinger Hill (Vinegar Hill Subdistrict)

The streets in this area were originally laid out to provide access to the two main mills that were located south of Highway 7 – Markham Mills and Glen Rouge Mill.

Markham Mills

The Milne family operated wool and flour mills from 1824 when Peter Milne acquired the property. Peter had no milling experience -- he ran a general store. His brother Alexander ran the woollen and flour mills. When Alexander married and set up his own mills at the corner of what is now Lawrence Avenue and Leslie Street (Edwards Gardens) in Toronto, Peter hired millers to run his site. Peter died in 1845, leaving his wife Elizabeth and their oldest son, Thomas, to manage the operation.

In 1866, a fire caused severe damage to the mills. Only the grist mill was rebuilt, later to be operated by Thomas Milne’s sons, Grant and Archie, under the name Milne Brothers. In the early 1900s, the brothers manufactured a breakfast cereal called Wheateen.

Archie built a steel and concrete arc dam in 1911 to generate power for the growing village. It was the first of its kind in the area. Its embankments were washed out by Hurricane Hazel in 1954.

Today, this area west of Main Street South is known as Milne Park.

Glen Rouge Mill

To the east of Main Street South, there was another grist mill operated by Archibald Barker.

Barker sold the mill in January 1857. There were a number of owners with full or half interest in the mill throughout the 19th century. Glen Rouge Mill was demolished around 1920. The site is now a conservation area.

Vinegar Hill

While there are many colourful theories on the origin of the name, the most likely explanation is that the steep incline of Main Street South was named Vinegar Hill or Vinegar Dip after a cider mill was constructed on the east side of the valley.

- 3. Marham Agricultural Fair (Vinegar Hill Subdistrict)

It’s not clear when the first Markham Fair was held, but there were fairs held in both Unionville and Markham by the mid 1850s.

A 45.7 metre by 15.2 metre, one-storey Agricultural Hall, or Crystal Palace, was eventually built within a fenced fairground on a farm owned by William Armstrong. Thousands of exhibitors and visitors learned of innovations in farm practices, took part in livestock, produce, and handcraft competitions and experienced the local farming community. Stalls, a grandstand, racetrack, ice rink, and exhibition hall, and other buildings were scattered across 12 hectares, making this site a landmark.

In 1873, more than 10,000 attended the fair. It was such a success that the Toronto newspapers described the Markham Fair as the fourth largest behind London, Guelph and Hamilton. The fairground was also used for sports such as lacrosse, baseball and hockey, along with other events such as travelling circuses. Parades along Main Street always ended at the site.

Plans for a new Crystal Palace and rink were in place by 1894. When finished, the new agricultural hall was two storeys, the lower floor was for vegetables and fruit, and the upper was for the “ladies’ exhibit.” The ice rink connected to the hall was the scene of many great hockey tournaments. In 1914, 3,000 people attended a match between Markham and the Riverside Hockey Club from Toronto.

Fair attendance soared and special trains brought visitors from north and south. The Methodist Church would feed 500 and 600 people, and many village residents opened their homes for the occasion. Hotels did a roaring trade.

On March 10, 1916, fire destroyed the ice rink, agricultural hall and ticket office. John Miller of Unionville was hired to build a new rink and agricultural hall later that year.

In 1977 the fairground was relocated to McCowan Road near Elgin Mills Road and the Markham Fair continues to be held every October. The Markham Public Library stands where the former fairground once was.

- 4. Highway 7 (Markham Village Subdistrict)

World War I changed transportation in Canada forever. Before 1914, the horse was still the primary means of moving people and goods. Steam railways were used for long hauls and to carry heavy freight, and electric railways or radial lines were expanding as a passenger and freight network.

However, the war effort relied on truck transport so much that after 1918, motorized vehicles quickly increased in popularity. Regional bus companies known as “rubber wheel” transport began to replace short-haul radial and railway service, and most plans for expanded radial networks were abandoned. In 1920, in response to growing demands to improve the provincial highway system, a Royal Commission investigated the increasing automobile and truck traffic.

Five years later, the construction of Highway 7 reached Markham Village. Grace Anglican church, which had faced Main Street, was moved and turned south to face the north side of the new highway. Because many properties could not be purchased or taken over by the province until the early 1930s, the highway did not completely pass through the region until that time.

Highway 7 is among Ontario's most important routes, particularly through Eastern Ontario where it is the only major through route north of Highway 401. At its peak, Highway 7 measured a total distance of 716 km in length. Starting in the 1990s, sections of Highway 7 were “downloaded” by the province to local municipalities. Although the opening of the toll Highway 407 parallel to Highway 7 has removed much of the through traffic, Highway 7 is still an important corridor to the City of Markham. In 2005, Highway 7 was made the second main artery for York Region's VIVA rapid transit service.

- 5. Stonehouse Robbery (Markham Village Subdistrict)

Edwin Stonehouse was 59 years old when the Red Ryan gang tried to steal a 1935 V-8 Chevrolet Master Sedan from his automotive business. As gang member Edward McMullen started to drive the car away, Edwin and his 22-year-old son James ran and jumped in. The Stonehouses and McMullen were fighting in the Chevy as they drove west on Highway 7. McMullen’s accomplices, Harry Checkley and Norman “Red” Ryan, pursued them in their Model-A Ford. It was snowing heavily and the roads were slippery. At some point, the Stonehouses succeeded in pulling the keys out of the ignition and throwing them into the snow. Shots were fired; the first hit James in the hand and the second hit Edwin. More shots were fired after which Edwin collapsed. He had been shot in the head by McMullen and James had taken a shot in the stomach.

The robbers fled in the Model-A which stalled half a mile away. At this point, a police constable drove past the Chevy and saw James and Edwin lying on the ground. He then reached the Ryan Gang trying to get their car started. When the constable approached, the gunmen fired five shots at his car, hitting the mudguard. The robbers started their car and fled, firing at the constable who was in hot pursuit. The police officer eventually abandoned the chase and went back to look after the injured men. Fifty-six pellet marks were found in the constable’s car, although he escaped injury.

It was only later that the crime was linked to “Red” Ryan and his accomplices and this resulted in a scandal that changed Canada’s parole system. Ryan had been sentenced to life imprisonment in 1924 and served part of his sentence at Kingston penitentiary. He managed to convince the public and a number of senior politicians that he had changed his ways, becoming a spokesperson for prison reform. He was paroled and moved to Toronto where he hosted a popular radio program denouncing his past criminal life. Meanwhile, his gang was terrorizing southern Ontario with armed robberies and safecracking. During this crime spree, Ryan killed six people. When officials realized how they had been made to look like fools by the “Jesse James of Canada,” the parole system was tightened.

- 6. Markham Village Churches (Markham Village Subdistrict)

The Impact of Church Union on Markham Village

In 1840, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church stood on what is now St. Andrew’s Cemetery on Highway 7, east of Main Street. Fire destroyed the church and a new brick building was opened in 1873 at 7 Washington Street.

In 1925, Presbyterians, Methodists and United Congregationalists voted whether or not to unite and become the United Church of Canada. The St. Andrew’s congregation voted for union, with a vote of 64 to 57. As a result, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian became St. Andrew’s United Church East.

Part 2: The Methodists

During the 19th Century, Methodism was the largest denomination in the area. By 1855, various Methodist sects had 11 chapels, three ministers, and about 22 preachers in the Village. One of these chapels was a Wesleyan Methodist erected in 1836 in the Vinegar Hill area. This was replaced by a red brick building at 32 Main Street North in 1862. The Vinegar Hill building was used as a town hall until 1882.

When the Markham Wesleyan Methodists joined the Church union in 1925, the 32 Main Street North church became St Andrew’s United Church West.

Part 3: The United Church

The formal union of the Presbyterian, Methodist and United Congregationalists took place on March 6, 1927. Morning services took place at St. Andrew’s United Church West (32 Main Street North) and evening services were at St. Andrew’s United Church East (7 Washington Street).

In 1950, the east church was purchased by the Markham District Veteran’s Association and St. Andrew’s United fully relocated to the west church

Part 4: The Presbyterians Post-1925

In 1925, about a third of Canada’s Presbyterians voted against unification. Instead, they formed the Continuing Presbyterian Church of Canada. Presbyterians in Markham Village conducted services in the Orange Hall at the northwest corner of George and Church streets until a new St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church was erected at 143 Main Street North in December 1926. The congregation expanded in the 1960s and a Christian education building was constructed in 1964. Continued growth led to further expansion in 2009.

- 7. Speight Wagon Company (Markham Village Subdistrict)

The company developed a line of farm wagons, trucks, carts, cutters, sleighs, grocery wagons, horse-drawn streetcars, and even baby carriages. There was a division producing doors, blinds, window sashes, sheeting, and flooring, and another for repairing and repainting old wagons. For a time, the company held the monopoly on the manufacture of coal wagons with non-detachable tires. They were filling orders from as far away as Fort Garry (now Winnipeg), Manitoba, and were hailed for contributing to the settling the West. The name Speight became well known for their high quality wagons.

Both patriarch Thomas Speight and his son James were community minded. Thomas was a school board trustee and James was involved with the village fire brigade, served on the municipal council, was the first reeve (the presiding officer of a village or town council) after incorporation of the Village in 1873, and was Warden of York County in 1875 – the year Thomas Speight died.

In 1882, the company was incorporated as a joint stock company, Speight Manufacturing Company of Markham Limited.

When the Canadian economy declined in the late 1880s, Speight Manufacturing accumulated debts that resulted in its sale in 1890. Thomas Heys and James Speight’s younger brother, Thomas Henry Speight, bought the assets and reopened as the Speight Wagon Company. By this time, 60 employees were making 200 wagons a month. There was a branch office and a distribution warehouse in Toronto and, after 1900, warehouses on both Jarvis and Ontario Streets. Another branch office opened in Fort William (now Thunder Bay).

As the 20th century unfolded, many wagon and carriage makers underestimated the impact of automobiles and mechanized farm implements. By the end of World War I, horse drawn vehicles had become obsolete. Those few companies with the foresight and capital to switch to automobile production would soon dominate the transportation industry.

In 1910, the business was bought by the Port Arthur Wagon Company but soon went into liquidation. The Markham factory was closed and used to store fire equipment until it was sold in 1917. What remained was demolished in 1976 to make way for a roadway and the apartments at 20 Main Street North.

- 8. Main Street (Markham Village Subdistrict)

By 1857, Markham Village was a mix of factories, shops, and dwellings with Main Street as its core.

More than 1,000 people lived and worked there. New construction was made easier thanks to the many carpenters, joiners, builders, masons, tinsmiths, coopers, pump makers, blacksmiths, cabinet makers and machinists in the village. An ironmonger and a window and sash factory were also near at hand. Transportation was taken care of by wagon and carriage makers, harness makers, and saddlers. Everyday needs were met by a boot and shoe maker, tailors, jewellery and watchmakers, a butcher, a baker, and general and dry goods merchants. Other needs were attended to by physicians, insurance salesmen, a dentist, postmaster, tax collector, and barrister. There were inns, a school, churches for every denomination and the local news was reported by David Reesor in his weekly newspaper, The Economist.

In 1871, the Toronto & Nipissing Rail Road arrived and a station was built to the north of the village. The railway gave villagers access to new markets and items not previously available without considerable effort and expense. Some shops and industries competed successfully; others did not. More elegant hotels and dining facilities were built catering to the travelling public.

The general prosperity of the village resulted in the space between the commercial district and the railway station being developed and the village was officially incorporated on January 1, 1873. An impressive Town Hall was constructed at 96 Main Street in 1881 – a symbol of the village’s continuing success. Markham Village grew again when Mount Joy Village to the north was taken over on January 27, 1915.

- 9. Markham Village and Town Hall (Markham Village Subdistrict)

The arguments in favour of a permanent Town Hall were many: court proceedings were being conducted on the third floor of a Village store, the municipal fire equipment was stored in a shed, the “municipal office” and Council Chambers could only accommodate about 10 people. In addition, Markham Village was expected to grow rapidly.

William Hamilton Hall, the proprietor of Franklin House, contributed part of his property at the southwest corner of Main Street North and Robinson Street for the project. Construction began in 1881 with John Anthony as the architect. The Freemasons and Oddfellows offered to pay almost half the $2,500 construction cost in return for a 99-year lease and their own lodge houses in the Town Hall.

Markham’s grand Town Hall opened in January 1882 and the first Council meeting took place there on January 16. For the next 60 years it acted as the centre of activity for the Village.

In 1946, the Town Hall was sold and the building became a cinema. The auditorium floor and staircase to the top floor were removed, the basement was altered to provide a concession area, and the facade was plastered over. The Freemasons and Oddfellows continued to use the building until the early 1950s.

In 1971, York Township became the Region of York and the boundaries of Markham Township changed. Some sections went to the Town of Richmond Hill; others to the Town of Whitchurch-Stouffville. What remained of Markham Township became the Town of Markham. Council Chambers moved to the former Township offices in Buttonville until 1990 when the Markham Civic Centre opened. The old Town Hall was bought by the Town of Markham in 1983 and restored in the mid-80s. It is now protected under the Ontario Heritage Act.

- 10. Morgan Park (Markham Village Subdistrict)

The Markham Horticultural Society was founded about 1920 with the mandate of beautifying the Village. The Society hosted an annual flower show and competition, arranged lectures, encouraged the improvement of private lawns, perennial borders, and shrubbery, “for which Markham is fast becoming famous,” and was responsible for the creation of (Railway) Station Park. In 1923, the Dominion Horticultural Council granted Markham Village official status as a Rose Demonstration Plot and Council permitted the Markham Horticultural Society the use of the north half hectare of Morgan Park as a rose plot. In April 1924, the Markham Rose Test Plot was planted with the newest, rarest and best varieties of roses from “many of the leading rose growers in England, Ireland, Holland and the United States.” More than a 1,000 rose bushes were expected to be set out that spring and more in the fall. The growers were interested in having new varieties tested in the Markham climate and shown to the public. The success of “Markham’s Rose Garden” was described in the Markham Economist and Sun on June 27, 1935:

With Markham’s Rose Garden a mass of bloom, the usual interest in this beauty spot is being taken by visitors and town people generally. Lovers of flowers and shrubs find in this well arranged and well kept garden a very great source of attraction while an occasional hour spent there affords much pleasure.

The rose garden soon attracted thousands of visitors. When King George VI came to Canada in 1939, an oak tree was sent from England and planted in the garden.

A bandshell was erected in the park for evening concerts performed by the Town band. Tennis courts, a bowling green, playground equipment, and a lighted ball diamond for minor baseball, softball, and ladies slow pitch were also added. In 1957, the rose garden was dismantled to make way for the Lions Club swimming pool that continues to be open during the summer months.

- 11. Robinson Farm (Markham Village Subdistrict)

William and Elizabeth Robinson settled in Ontario shortly after the American Revolution. In July 1806, they bought 81 hectares of farmland in Markham Township. William died in 1824 and over the next few years, the land was split amongst their children with their son John acquiring the southernmost part of the property.

In 1834 and 1835, John acquired land adjacent to his farm on what is today the west side of Main Street North. Some of this was for the development of the tannery at the end of Robinson Street. The Robinsons soon became leading manufacturers of leather goods and prominent in local politics and community life.

One of John’s sons, William, farmed part of his father’s property. He had married Elizabeth Reesor in 1869 and it was Elizabeth who had the house at 1 Orchard Street built in 1887. Following William’s death in 1922, 60 hectares were bequeathed to his son, James G. and 18 hectares to his daughters Hannah, Mary, Edith, Christine, Annie, and Helen. The daughters also acquired the house on Orchard Street. Sadly, James G. died shortly after the transfer.

In 1923, the daughters sold approximately three hectares to Austin Graham, who then sold them to the Village of Markham. This is the property at the southeast corner of Parkway Avenue and George Street that became Morgan Park.

Albert Richard Lewis purchased James G’s 60 hectares in 1926. As there were no dwellings on the property, Albert and his wife Margaret lived in a rented house on Wales Avenue. Their first dwelling at the farm began as a barn and had a parlour room added to the front. By the early 1930s, a vacant house from a neighbouring farm had been moved to the north side of the barn. Today, this house remains at 27 Parkway Avenue.

When Albert and Margaret’s son Carman founded Markham Dairy, he used the first dwelling as the bottling plant. Carmen Lewis died in 2009 and is commemorated in the naming of a park at Parkway Avenue and Paramount Road.

- 12. Markham Village Public School (Markham Village Subdistrict)

Education in early Canada followed the British model of elementary schools that operated privately. They were attended only by those who could afford the fees. The Common Schools Act of 1816 permitted local residents to build a school, provided they had a minimum of 20 pupils, and elect trustees to hire a teacher and manage the school. The government agreed to contribute to the teacher's salary.

In the 1840s, the school system was reshaped by a series of school acts, beginning with the Common School Act of 1841. This Act doubled the size of government grants and introduced compulsory property taxes as a means of funding elementary schools. In 1846 to 1847, the Village of Markham built a frame schoolhouse at or near the site of Franklin Street Public School.

Elementary school fees were eliminated across Ontario in 1871 and resulted in the removal of another barrier to accessible education. However, secondary school fees were not dropped until half a century later.

In 1891, school attendance for children between the ages of eight and 14 became mandatory. (The mandatory age was extended to 16 in 1919.)

After the frame schoolhouse was severely damaged by a fire in 1886, it was replaced by a four room brick building that was named Markham Village Public School. Today, this structure is the west wing of the current school at 12 Franklin Street.

On February 28, 1906, the brick school was gutted by yet another fire. Students were temporarily accommodated in short-term facilities in the Town Hall, the Orange Lodge and Grace Anglican Church.

The building was enlarged in 1951 to accommodate a growing student population. The name was changed from Markham Village Public School to Franklin Street Public School in the 1960s when schools were being named for their street location.

- 13. Henry R. Wales Dwelling and Carriage Works (Markham Village Subdistrict)

Henry R. Wales was English by birth but moved to Canada with his family when he was nine years old. He moved to Markham in 1846 to work in a foundry but soon opened his own carriage manufacturing business that was located in front of the fine house, ‘Maple Villa,” named because of the maple trees that still cover the landscaped lawn and line the drive. His brothers, Josiah and George, worked with him.

The business grew rapidly and Henry Wales saw the benefits. He was able to retire 20 years before his eventual death on December 13, 1905, at the age of 83. During his life, Wales was very involved with public life although he never sought office; in fact, he turned down many offers to run.

In the early 20th century, the Wales Carriage Shop was taken over by Levi Webber, Henry’s son-in-law. Webber concentrated on the repair of carriages and wagons rather than their manufacture. He also specialized in the repair of bicycles and, after 1915, the repair of automobiles. He suffered a stroke in 1923 and another enterprising business came to an end with the buildings being torn down. However, Maple Villa remains. Because it has a deep setback from Main Street North, it was obscured for many years by buildings along the street. After leaving the hands of the Wales family, the house was owned by Arthur White, “Derby” Riev, Gordon Gower, and Mrs. L.E. Wratten who restored the house after purchasing it in 1964.

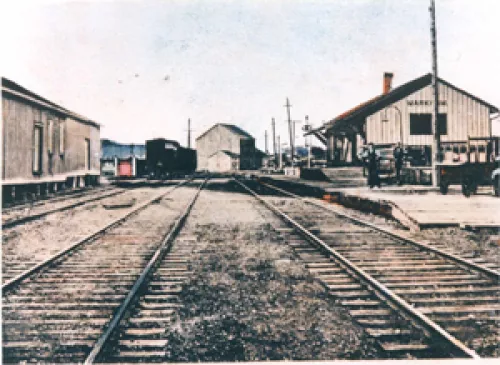

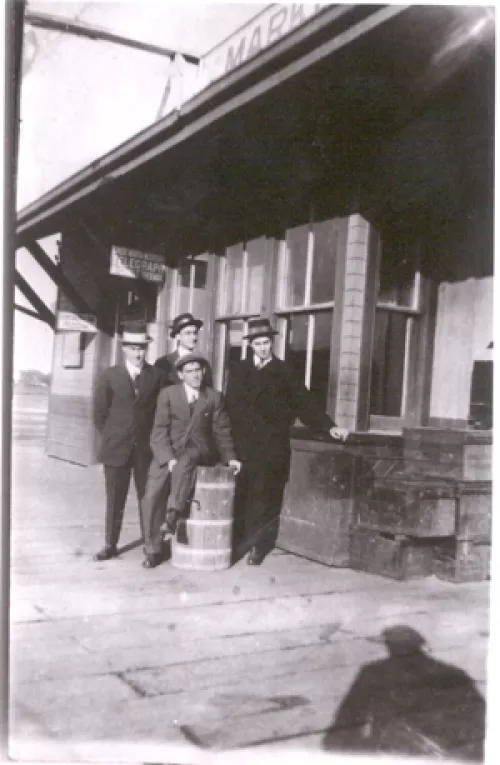

- 14. The Railway in Markham (Markham Village Subdistrict)

The Toronto & Nipissing Rail Road (T&N) was initially meant to travel all the way to Lake Nipissing, but lack of government funding terminated the line at Coboconk.

The T&N was built with a 42-inch “narrow” gauge track. At the time, narrow gauge cost less to construct and maintain, and was considered to be safer and faster ,than the broad or “standard” gauge of 56.5 inches.

The distance between the Village and the railway station to its north was at first a source of complaints, but the area quickly developed. The Markham Economist claimed:

There never was a time of more genuine prosperity than we have at present. Every shop is filled with busy hands. The click of the hammer, the buzz of the saw, the puffing of steam, is heard in every direction – everybody is working for everybody.

It further made a prediction that:

By the wise management of our Railroad, we believe Markham may ultimately become an important suburban town to Toronto.

Communities bypassed by the rail line, such as Sparta (later renamed Box Grove), started to decline.

This initial enthusiasm was soon dampened by complaints against T&N’s high tariffs. The Speight Wagon Company shipped wagons 15 miles to a northern route rather than pay the tariffs. Sometimes the tariffs were doubled for no stated reason. However, the wagon making and carriage industry was greatly bolstered by the arrival of the railway. Companies such as Speight’s could develop a nationwide clientele. There was also increased demand locally for vehicles to move products or produce to and from the station.

After T&N joined with the Midland Railway Company in 1882, the track was changed to a standard gauge. Now, larger cars and heavier loads could be pulled.

For 50 years, the railway played an essential role in the growth of Markham Village, with two or three passenger trains daily from Monday to Saturday, as well as freight and mail trains. But as the number of automobiles and trucks increased in the 1920s, railway companies began to lose their monopoly on passenger, mail and freight transportation.

- 15. The History of Mount Joy (Mount Joy Subdistrict)

Members of the Ramer family were not the only successful business owners in the 1800s. There was Abraham T. Moore and Son’s pump factory, Peter Milne’s Markham Mills, and John Monkhouse’s planing mill. David Byer founded a skin cancer treatment institute that evolved into the Byer Cancer Hospital at 300 Main Street North. In 1890, Aretus Urmy opened a general store at 266 Main Street North. A school was erected in 1835. A later school near the northwest corner of 16th Avenue and Main Street North was later converted for use as the Markham Museum.

The arrival of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway in 1871 began a major period of growth and many parcels of land were sold for new homes and businesses. Today, the southern part of Peter Street still contains many houses dating from the late 1800s.

In February 1907, Mount Joy became a police village. This was a form of municipal government created in the early 20th century for communities where the finances or population were not enough to create a village. A police village was not incorporated by the provincial government but by a by-law of the district or county government. It had its own elected governing body of trustees, which could establish fire and safety services and regulations, erect streetlights, and build sidewalks, but otherwise remained within the jurisdiction of the higher level of government.

Mount Joy was given over to the Village of Markham on January 27, 1915, with terms set by the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board. The Village of Markham was to supply Mount Joy with, “electric light for domestic use, street lighting and water.” Other provisions such as exempting Mount Joy from debts incurred by Markham, and holding the property assessment values for 10 years on agricultural property, were among other concessions and guarantees.

- 16. Health Care in Mount joy (Mount Joy Subdistrict)

Byer Cancer Hospital

Christiana Byer used her father’s “old Mennonite remedy” to “cure” skin cancer. The “remedy” was placed on the tumour or growth to “draw the cancer out of the skin.” After the cream was removed, a healing ointment was applied. The process was described as painful and often left the patient disfigured. To exhibit the effectiveness of the remedy, the growths were often preserved in jars.

Since the hospital was not operated by a physician, there was no fee for the treatment. Revenue was generated by charging patients room and board. When Christiana’s son Peter graduated from medical school, he expected to run the hospital. However, he was denied a medical licence when he refused to divulge the details of Byer Hospital’s cancer remedy. The hospital was closed and Peter moved to Michigan to work in the Chrysler Automobile Corporation laboratory. The property was sold in 1922.

Springdale Mineral Springs or Baths

A brochure from 1886 and 1887 explains:

The advantages derived by the afflicted in the treatment of chronic and lingering diseases by the free use of Mineral Waters and bathing, combined with plain country diet and entire freedom from the cares and anxieties of everyday life ... has now come to be an acknowledged fact. By their internal use the stomach is washed out, the secretion of bile, saliva, pancreatic juice, perspiration and urine is increased, thereby promoting the elimination of [waste] matters from the blood and tissues, thus facilitating the building up of the various tissues of the body by the more ready {digestion] of foods. By their external use, in the shape of bathing, they prepare the skin for perspiration by softening and purifying it and increasing its circulation, stimulate the organic functions, promote absorption, and calm nervous and muscular irritability. The internal and external use of Springdale water has been pre-eminently serviceable in the treatment of dyspeptic troubles, particularly those arising from a sluggish circulation of the liver, in rheumatic gout, chronic rheumatism, and in convalescence from rheumatic fever, in chronic skin disease, the various forms of buric acid, gravel, and chronic affections of respiratory, digestive and genitor-urinary system. . . .Good enjoyable country board and lodging can be obtained on the premises.